Reentry Courts have a unique position among Problem-Solving Courts in their relationship to state government. Reentry Courts are almost entirely creatures of the state (at least, those dealing with returnee’s from state prison, are largely under state jurisdiction) and rely on state judicial, legislative, and executive support for their existence.

What follows is the first in a series of articles that explore the critical relationship between Reentry Court and the State.

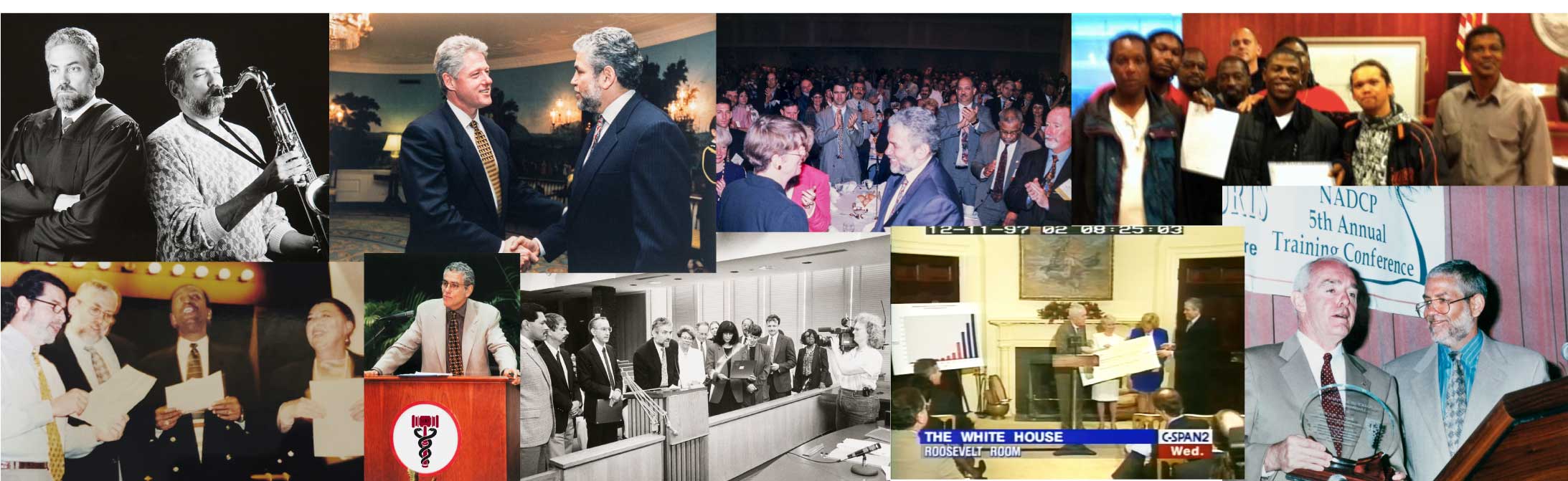

Fifteen years ago, few people who were aware of Drug Courts understood their extraordinary promise. Initially nearly everyone believed that Drug Courts were and would remain a purely local phenomenon, one fostered by local innovation and commitment alone, with little state or national impact. The success of the drug court, has resulted in heightened state interest in them, as well as their progeny, Problem-Solving Courts (special courts that use the drug court model to address other serious offender issues, ie., DUI, Domestic Violence, Mental Health, Veterans Courts, etc.). It is clear Problem-Solving Courts, like Drug Courts, can no longer be considered “individual programs”, isolated from the rest of the state criminal justice system. Indeed, Drug Courts and Problem-Solving Courts have gone “mainstream” as the Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators unanimously endorsed them in years 2000, 2004, and 2009

Initially however, state governments had been relatively uninvolved in the development of drug court programs. Many state agencies, as well as the organizations that represented them on the national level, expressed indifference that at times bordered on opposition to the development of the Problem-Solving Court model. State Judicial Leaders were typically cool to the Problem-Solving Courts concept. The drug court model was new, thought expensive and untested by reliable evaluations. In 1994, the National Center for State Courts (NCSC), representing the Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators, rejected the notion of the drug court as a “special” court.

Soon after, National and State Judicial leadership reversed course, with NCSC and the nation’s judicial leadership providing strong support and leadership on behalf of the problem-solving court model, (see: CCJ/COSCA Resolution). There were many reasons for their pro-active role on behalf of Problem-Solving Courts. Without state judicial leadership’s guidance, State Judicial Administrators feared that courts would develop inefective programs, while consuming scarce court resources. There were concerns that programs developed by one judge would be undone by the next. They worried about judges becoming media “stars” in their communities, and neglecting their other judicial duties. They legitimately wondered how these programs could survive without a level of standardization and institutionalization of practices and procedures.

Similarly, State Departments of Alcohol and Drugs had been slow to support the drug court concept. Funding in particular had been a significant issue. Initially, reluctance seemed be based on a generally held belief among treatment agencies that the criminal justice system, with its greater resources should be responsible for funding drug treatment through the criminal courts. There was also the concern that the criminal justice system would dominate any treatment program they participated in. They worried that the courts would overwhelm treatment agencies with clients without corresponding new resources. They were concerned that individual courts would provide limited and inadequate assessments and treatment to participants. They feared that the criminal justice system would ignore the scientific research on effective treatment and demand prison for those who didn’t conform to court mandates. Those fears have receded with the development of effective court/treatment partnerships and the emergence of drug court judges and other practitioners as effective advocates for the expansion of treatment resources.

Governors and Legislatures also felt the need to react to this new phenomenon. They were certainly aware of the extraordinary media coverage and political support from across the political spectrum. But, like everyone else in state government, they were concerned that Problem-Solving Courts would consume disproportionate state funding needed for other purposes in times of limited funds. They questioned whether Problem-Solving Courts were truly effective and cost-efficient.

Of course, state policy makers were not the only ones who saw the need for state involvement. While deeply ambivalent about the extension of state power and influence over what were grass-roots community-based courts, Problem-Solving Court judges and other practitioners welcomed state financial support. Ultimately, judges looked to state leaders to help them legitimize their programs and convince their colleagues and county administrators of the importance of their work. Treatment providers looked to the state for resources and direction. Probation and parole officers requested resources to maintain reasonable caseloads. And defense attorneys and prosecutors sought political support and affirmation for their non-punitive approach and non-traditional roles. For the most part, all agreed that a statewide presence was needed. The form that involvement was to take was a more difficult issue to determine.

The limitations of a strictly local Problem-Solving Court program are now clear. Even with the commitment and assistance of the federal government, the impact of Problem-Solving Courts, in both quality and quantity of services and numbers of participants reached would be severely limited without strong state financial and political support. A statewide Problem-Solving Court policy is now generally accepted as necessary in order to institutionalize court policies and procedures, stabilize program structures, standardize treatment requirements, and expand eligibility to those who most need assistance, the high risk offender.