April 29,2013

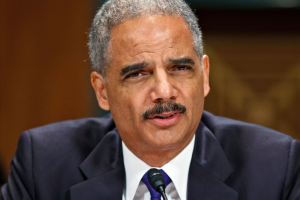

[The Second Chance Act, administered by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), within the Department of Justice (DOJ), has provided hundreds of millions of dollars for reentry projects in every state of the union. Below, the National Reentry Resource Center, provides highlights of BJA’s administration of the “Act” (click on image on left for PDF of National Reentry Resource Center Document)]

[The Second Chance Act, administered by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), within the Department of Justice (DOJ), has provided hundreds of millions of dollars for reentry projects in every state of the union. Below, the National Reentry Resource Center, provides highlights of BJA’s administration of the “Act” (click on image on left for PDF of National Reentry Resource Center Document)]

The Second Chance Act: The First Five Years

This month marks the five-year anniversary of the Second Chance Act, the landmark legislation authorizing federal grants to support programs aimed at improving outcomes for people leaving prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities and reducing recidivism. The bill also funds research and evaluation projects and created the National Reentry Resource Center, a clearinghouse of information relating to prisoner reentry. Through its broad scope and innovative approach, the bill has had a significant impact on all stakeholders: individuals and families in need of services; communities and governments seeking strategies to increase public safety and reduce costs; researchers looking to inform, advance, and disseminate their work; and practitioners interested in enhancing their programs and sharing best practices with others in the field.

The grant program currently funds eight different types of projects: demonstration projects involving the planning and/or implementation of a reentry initiative for adults or juveniles, mentoring services for adults or juveniles, family-based substance abuse treatment for incarcerated parents, reentry courts, programs targeting individuals with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders, funding for state departments of corrections to achieve recidivism reductions through planning and capacity-building, evidence-based strategies in probation supervision, and programs providing training in technology careers. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) manages the juvenile demonstration and juvenile mentoring projects, while the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) of the U.S. Department of Justice manages all the other projects.

To date, BJA and OJJDP have awarded nearly 500 Second Chance Act grants to state, local, and tribal government agencies and nonprofit organizations across 48 states and the District of Columbia, totaling nearly $250 million. Representing a wide range in geography, size, and program design, the grantee programs display the different ways that reentry strategies can be applied in jurisdictions.

Reflecting the importance of reentry as a process that begins during incarceration, grantees must serve individuals both in pre-release and post-release stages. According to BJA’s latest performance reports on its Second Chance Act grantees, the grantees served more than 11,000 participants in pre-release programs and nearly 9,500 participants in post-release programs from July 2011 to June 2012. The vast majority of participants are assessed as medium or high risk, which is in line with research that shows that focusing services and resources on higher-risk individuals has the strongest impact on recidivism.

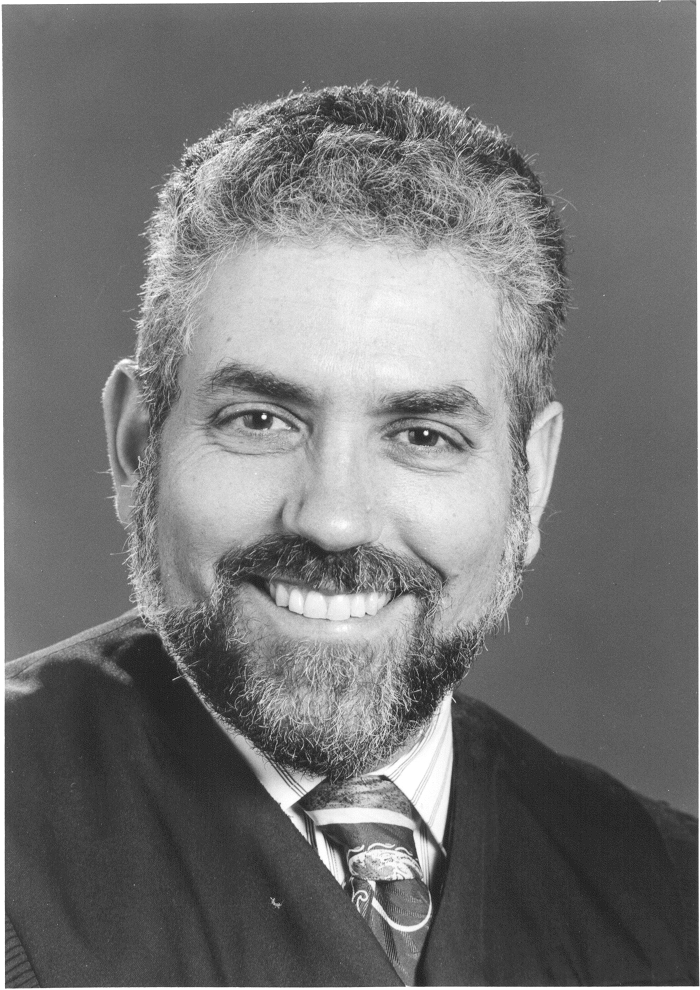

Some programs have already seen reduced recidivism rates among the people they serve within the first few years of the grant program. For the Harlem Parole Reentry Court in New York, which has received two Second Chance Act grants, preliminary results from an ongoing evaluation showed that the rate of reincarceration at 12 months after release of 14.7 percent for program participants was 24 percent less than a comparison group’s rate of 19.3 percent. The reentry court serves medium- and high-risk adults in Harlemand offers a combination of intensive case management, parole supervision, judicial intervention, clinical services, and other support services. Furthermore, the program employs the evidence-based practice of graduated sanctions and incentives to promote compliance and accountability.

In addition, Second Chance Act grantees have achieved positive outcomes on a number of other measures, including employment, education, family reunification, and pro-social relationships. For instance, the Girl Scouts of Eastern Oklahoma, a 2010 Adult Mentoring grantee, has found that 74 percent of the participants who received employment development services have since obtained employment.

The positive impact of the Second Chance Act can perhaps be best conveyed by the program participants themselves. Since early 2012, the Council of State Governments Justice Center has interviewed program administrators and participants and shared their individual stories in the National Reentry Resource Center (NRRC) website and newsletter. The people featured have included: Wade, a Los Angeles man in his fifties whose participation in the Amity Foundation’s mentoring program helped him overcome his addiction to heroin and become a mentor himself; Frankie, a father in New Mexico who enrolled in PB&J Family Services’ program while in prison and received help finding employment and parenting pre- and post-release; and Janelle, a young woman with co-occurring bipolar and substance abuse disorders who found a job and returned to school after receiving treatment from the Ohio Department of Youth Services’ Second Chance Act-funded program in Franklin County. Each of these stories represents the success and promise of the Second Chance Act and initiatives focusing on prisoner reentry across the country.

Also funded by the Second Chance Act, the NRRC has made great strides in advancing reentry work by promoting and disseminating key information for practitioners, researchers, policymakers, and others in the field. In addition to the website and newsletter, the NRRC offers webinars each month. Recent topics have included work release centers, electronic technology in supervision, and the needs of women in the criminal justice system. The NRRC also produces reports and guides to inform reentry work in practical and constructive ways. Its most recent product is a series of checklists with targeted guidance for state corrections departments and policymakers on building reentry initiatives to reduce recidivism.

The Second Chance Act was signed into law by President George W. Bush on April 9, 2008, after receiving bipartisan support in both chambers of Congress. The bill authorizes up to $165 million per year in grant funds.