May 6, 2013

A distinctive article, written by Harold Pollack, Eric Sevigny and Peter Reuter, and published in the Huffington Post was reviewed on this website last week (The Trouble with Reentry Courts…). It described how drug courts, while reaching half of U.S. counties, don’t work enough with the population in greatest need, the high risk drug offender or serious offender with a dependence on drugs and/or alcohol. A recent proposal from the Bureau of Justice Programs (BJA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) may unintentionally institutionalize that unfortunate circumstance.

A distinctive article, written by Harold Pollack, Eric Sevigny and Peter Reuter, and published in the Huffington Post was reviewed on this website last week (The Trouble with Reentry Courts…). It described how drug courts, while reaching half of U.S. counties, don’t work enough with the population in greatest need, the high risk drug offender or serious offender with a dependence on drugs and/or alcohol. A recent proposal from the Bureau of Justice Programs (BJA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) may unintentionally institutionalize that unfortunate circumstance.

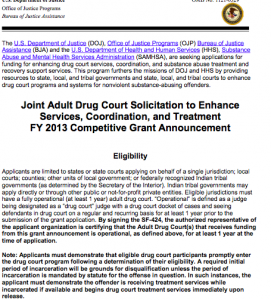

The most striking feature of that proposal is a restriction that has only been part of the Drug Court Funding Program since 2012: “Note: Applicants must demonstrate that eligible drug court participants promptly enter the drug court program following a determination of their eligibility. A required initial period of incarceration will be grounds for disqualification unless the period of incarceration is mandated by statute for the offense in question. In such instances, the applicant must demonstrate the offender is receiving treatment services while incarcerated if available and begins drug court treatment services immediately upon release (click on image on the left for a PDF of the BJA/SAMSA Request for Proposal).

Knowing that drug courts are intensive programs, specially designed to work with high risk offenders, who often have serious and/or violent criminal histories, the restriction noted above appears ill-advised. We know that the Congress restricts federally funded drug court programs to non-violent offenders (42 U.S.C. 3797u-2).Only Congress can change that ill-advised restriction. To add that, those who serve a term in custody are also prohibited from BJA/SAMSA funding appears to contradict the RFP’s rationale. From the text at page 7; “Grant funds must be used to serve high risk/high need populations diagnosed with substance dependence or addiction to alcohol/other drugs and identified as needing immediate treatment”.

This may be a classic example of unintended consequences. The relatively new provision, admirably encourages jurisdictions to reduce their reliance on incarceration as a response to drug dependence, by prohibiting drug court participants from being sentenced to custody. Unfortunately, it may have a far greater impact on the demographics of the offender class entering federally funded drug courts. Many drug dependent, high risk offenders, will have committed serious offenses (but not violent offenses) and have extensive criminal histories. To most judges, their criminal behaviors cry out for a custodial response. To the more enlightened , they also cry out for involvement in an intensive drug court program. What now appears to be the case, is that that an otherwise eligible drug court participant, if sentenced to drug treatment in custody, may not be transitioned into a drug court program on that same case post custody. Of course, savy, experienced drug court judges will find their way around the restriction. But the principle (so bolded) will have its impact upon the elligibility requirements of a great many drug courts.

Once again, these are the serious, high risk, high need drug dependent offenders that the research says need to be in drug court programs. In the real world, a petty thief, or car burglar, with a long history of similar crimes will almost always receive time in jail as a consequence of their current and/or past criminal behaviors. That might be a day, a week, a month , a year in county jail, or a term in state prison. Under the new grant restriction, an otherwise appropriate candidate would be excluded (unless he met the limited, mandated incarceration exception to the prohibition; see bolded text above).

This restriction will close the door to many if not most serious offenders with drug dependencies, who might face a term of custody. It seemingly precludes a collaborative and hopefully seamless application of proven drug court practices for those individuals while in custody and upon release and transition to a drug court program through probation or parole services.. It is not an effective approach to reducing recidivism or protecting society (these folks will soon be in your community with or without the intensive supervision and treatment provided by a drug court).

An American University Technical Assistance Project Report, “LOOKING AT DRUG COURTS AFTER TWO DECADES”, published in July of 2012, provides an important historical context. Drug Courts need to “continually move to the more difficult populations – defendants whose drug use is fueling criminal behavior and who may have criminal histories that might have barred them from the program in the past.”

[This article is an independent analysis of 2013 BJA/SAMSA grant funding for Drug Courts; it was not written with the knowledge, consultation, or approval of any other persons or organizations]