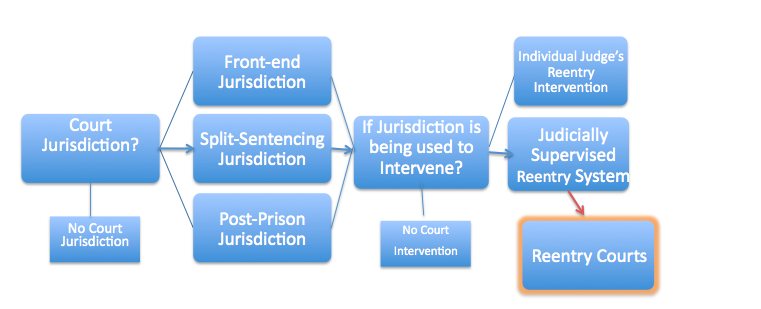

“Best OF” Series: Published in February 2012, this primer on State Court Jurisdiction is an important introduction into potential opportunities for court involvement in prisoner reentry

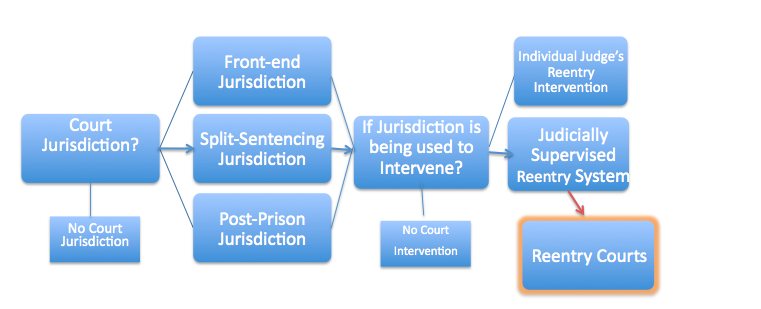

The “Court Jurisdiction Chart” (above) is designed to help you analyze whether your state has the potential for a Court-Based Reentry System (or Judicially Supervised Reentry System) and/or Reentry Court

1. COURT JURISDICTION

State court or Judicial connections to prisoners and ex-prisoners are much more common than generally believed, among the 50 states. State courts typically have some jurisdiction to intervene in prisoner reentry into the community, but rarely use that authority. Furthermore, relatively few such connections are organized into a systemic program that coordinates court or judicial intervention with community and correctional intervention.

While reentry court may be the best known of court based reentry systems, there are other systemic connections that exist between the court and prisoner/ex-prisoners, that have a substantial impact themselves or hold the potential for such an impact.

If your state does not provide your courts with the jurisdiction to intervene in prison reentry, the likelihood that you will be able to do so is small. A number of states have collaborative agreements or MOU’s with corrections and/or parole authorities that allow the court to either supervise the reentering prisoner directly or do so when the ex-prisoner has picked up a separate offense that the court does have jurisdiction over. There is also the possibility that your state legislature may give authority to your courts to intervene in prison reentry (.i.e California has made major changes to its reentry system, giving its courts jurisdiction over most prison sentences and parole violators).

2. COURT JURISDICTION: INTERVENTION POINTS

When the court intervenes is probably the most important factor in determining the level of care, resources, and supervision appropriate to individuals reentering the community. For obvious reasons, interventions after four months of a custodial sentence are likely to be far less intrusive or intensive than an intervention after four years of prison.

A. FRONT-LOADED (PREENTRY) JURISDICTIONS

The most obvious and immediate state court contact point is an early intervention; ordering a convicted felon to state prison immediately before or after sentence has been imposed, for an evaluation, assessment, or other purpose. While this power is found in most state courts, individual judges most often use it, on a case-by-case basis.

It is also used in a number of states, to intervene in a probationer’s drug usage or other criminal behavior, as part of a Reentry Court or other court-based intervention program. Frontloaded Courts (sometimes called Preentry Courts), typically work with participants who spend relatively short terms in prison (30 days to 4 months), although some front- loaded programs can sentence felons for up to one year in prison or other custodial setting. Of all Reentry Court participants, those engaged in a front-loaded reentry program, are most likely to have family, friends, jobs, skills, and connections to community, thus requiring the lowest level of court involvement and program intensity (a tier one intensity court).

B. SPLIT SENTENCING JURISDICTION

A number of states allow the judge to determine at sentencing, the prison term and probation supervision to follow. Some courts can change the split while the offender is serving his/her prison term (.i.e Ohio).

Several Reentry Courts use this jurisdiction model as a basis for their Reentry Courts (i.e. Indiana, Texas, Ohio, California). This is typically a hybrid or second tier reentry court, where some participants spend substantial terms in prison while others do not (a split prison term typically has a minimum of 1 year). A good risk/needs assessment can determine the court resources and intensity level required to reintegrate the split sentence offender into the community (considered a second tier intensity court).

C. POST PRISON JURISDICTION

Post Prison Court-Based Reentry Systems are thought to be closest to the established reentry court model. The prisoner finishes the prison term, is released early to enter a halfway house and Reentry Court (.i.e Nevada), or enters the Reentry Court when he/she violates their parole/probation (i.e. California)

3. NATURE OF THE “JUDICIALLY SUPERVISED INTERVENTION”?

Court intervention can be done in an ad hoc fashion, based on the discretion of an individual judge or part of a systemic process, where decisions are made and resources and staff allow for substantial numbers of program participants.

A. INDIVIDUAL JUDGE’S REENTRY INTERVENTION

Where the court has jurisdiction to do so, the intervention of an individual judges may recall a prisoner from prison, split a prison sentence, or release a prisoner early. This is often the decision of an individual judge, often operating without standards, guidance, or program staff, on a case by case basis. This use of this authority is uncommon in most states.

B. COURT BASED REENTRY

An organized court system or program requires court resources, and staff to intervene on a regular basis, to reduce a prison term (or other custodial term). Often the court system in question is a “Drug Court, or other problem-solving court, that makes use of “prison or other custodial setting to provide treatment, rehabilitation services, supervision, or other services.

4. REENTRY COURTS

This is a high intensity court-based reentry system, that often deals with ex-prisoners who have spent substantial periods of time in prison (typically 3 years or more) and are high risk offenders with serious and/or dangerous criminal histories. While reentry courts can be established at any one of the three intervention points (described above), the post prison segment is often used.

The court uses evidence based practices to determine the risk and needs of the offender and appropriate responses. Reentry Courts deal with the whole person, recognizing that participants often need significantly more than drug treatment; programs that provide room and board, cognitive behavioral therapy and family counseling, physical and mental health assistance, education and skill building and other rehabilitation services.

Importantly, the high risk, long – term prisoner often needs a reentry court to provide a surrogate community until real integration in the community can be accomplished. This 3rd tier Reentry Court demands a lot of the long term prisoner, requiring 40+ hours of pro-social activity per week and constant contact with court, counselors, and recovery community.

[email protected]

Professor Hale’s analysis describes NADCP as the “Champion” Non-Profit Organization in its field. What does it have to do with reentry courts and court-based reentry systems. The answer is that it does and it doesn’t.

Professor Hale’s analysis describes NADCP as the “Champion” Non-Profit Organization in its field. What does it have to do with reentry courts and court-based reentry systems. The answer is that it does and it doesn’t.