Evidence-based Sentencing systems [PDF]

Judge Jeffrey Tauber; jtauber@reentrycourtsolutions: 9/30/12

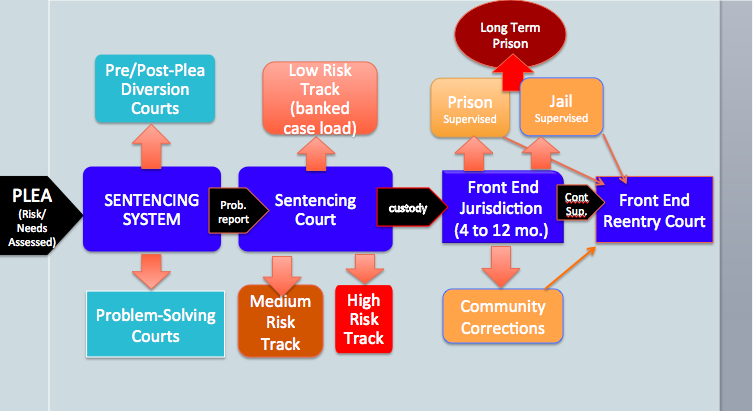

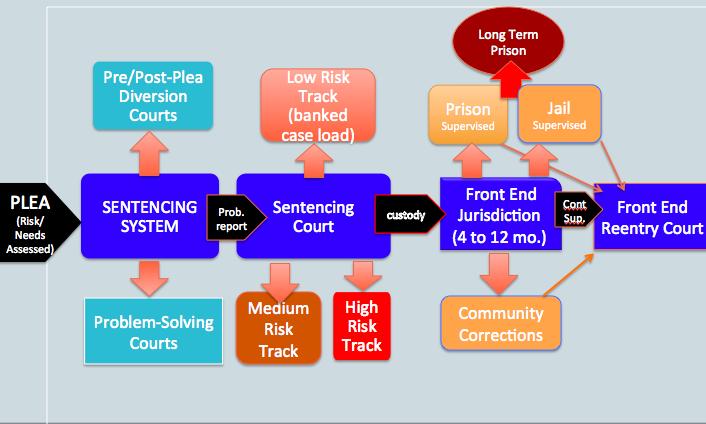

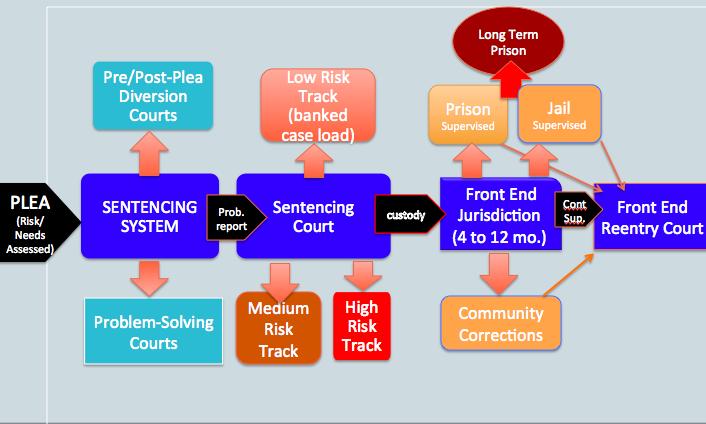

We have developed evidence based practices for the sentencing of offenders (based on voluminous research), but are still reticent to apply those practices where they will do the most good, in making sentencing decisions. Rational approaches to sentencing that provide different levels of supervision, treatment, rehabilitation, and assistance for felons are attainable and in effect in some states and jurisdictions. [[he Diagram below is used in this article as an example of a basic evidence-based sentencing sysytem]

Part 1: Evidence-Based Sentencing Practices

In 2009, the PEW Center for the States published an excellent treatment on Evidence Based Sentencing Practices (EBP), authored by Judge Roger Warren (ret.), President Emeritus of the National Center for State courts, “Arming the Courts with Research: Ten Evidence Based Sentencing Initiatives to Control Crime and Reduce Costs”. To summarize, nearly all sentencing courts are in essence, reentry courts (or court based reentry systems), and ought to be structured to facilitate the ultimate return of the offender to the community as a non-recidivist, productive citizen.

According to the PEW Monograph, every sentencing ought to take into account the most recent research, described as Evidence Based Practices (EBP). Those sentencing principles, (as described by the PEW Monograph) state that (1) Reduced Recidivism should be an immediate goal of sentencing, (2) Recidivism Reduction Options be available to the Court, (3) Sentencing be based on Risk/Needs Assessments, (4) Community Corrections be Evidence Based, (5) Services and Sanctions be integrated, (6) the Court be aware of Available Sentencing Options, (7) Court Officers be trained in EBP, (8) Court responses to probation violations be immediate, certain, consistent and fair, (9) Court hearings be used to provide incentives to motivate Offender Behavior Change, and (10) the Court Promote Collaboration among Criminal Justice Agencies.

Clearly, individual judges and courts will have have difficulty implementing many of the proposed initiatives. Only a systemic problem-solving approach is likely to successfully implement “Evidence Based Sentencing Practices”. (PEW declares as much on page two of the monograph; “the failure of mainstream sentencing policies….. has motivated many state judges, prosecutors, and corrections officials to establish specialized ‘problem-solving’ courts over the past 20 years to reduce recidivism”). Expecting individual judges to independently develop the resources, skills, and competencies to become proficient in Evidence Based Sentencing Practices is unrealistic.

That does not mean that every court needs to have the same level of resources, staffing or sentencing options. The question for most jurisdictions is what level of Evidence Based Sentencing Practices can they incorporate into their court, and that is appropriate for their community. A judge in a rural jurisdiction will have vastly different sentencing needs than a city with dozens of judges. And a low risk offender will have a very different relationship with the court than a high risk offender or an offender with a violent history.

Part 2: The Single Sentencing Court Team Concept:

One common feature that should define the Systemic Sentencing Model, is that the same judge and court team deal with the sentenced offender (to the extent possible), as part of a seamless supervision, treatment, and rehabilitation system, that runs from sentencing, through custody, through community supervision. The first of such systems go back more than 20 years to the dawn o the Drug Court era. It was widely understood that the sentencing and supervision of drug offenders was dysfunctional. There was little coordination in the court’s dealing with the drug offender, the offender rarely saw the same judge or court personnel twice, and there was little system accountability and therefore far too little offender responsibility and compliance ( Drug Courts: a Judicial Manual, J Tauber, California Center For Judicial Education and Research Journal, Summer 1994; click on facsimile on the left to review Section 30; on Structural Accountability)

We still live in a largely uncooperative world of competing government departments, uncollaborative programs and agencies, and weak sentencing follow-through by the courts and relevant agencies. As noted in Part 1, its unrealistic for individual courts to develop the advanced capabilities necessary to develop evidence-based sentencing practices (“Arming the Courts with Research: Ten Evidence Based Sentencing Initiatives to Control Crime and Reduce Costs”, a PEW monograph, Judge Roger Warren, ret.).

What is necessary, is for a jurisdiction to focus a single judge and court team (or in a larger jurisdiction, a dedicated cadre of judges and staff) to the task of applying evidence based practices to sentencing courts. There is no reason to use a different approach or rationale than that developed and successfully applied to drug courts and other problem-solving courts across the nation. A sentencing court’s effectiveness ultimately depends on a jurisdictions willingness to provide a rational, system-wide, coordinated approach to sentencing (It could be argued that much of the success of Hawaii’s PROJECT HOPE, rests on its systemic approach to felony probation supervision).

Some may feel it unnecessary for all felony sentencing and/or supervision to be handled by a problem-solving court. The advantages already described in such a system make it a very attractive alternative to the current somewhat haphazard process. What may be more surprising is the potential for savings to the court. Because the sentencing system will look to a validated risk/needs assessment tool to assist its sentencing decisions, it will be possible to create sentencing tracks for low risk/low need offenders that involve minimal resources and staff, allowing what limited resources that exist to be applied to high risk offenders with the greatest need and potential for harm.

In fact, low risk offenders may not be actively supervised by the court at all, after the individual makes a single supervision appearance before the judge after sentencing. On the other hand, a high-risk offender with a history of violence may be required to have weekly contact with the court and extensive contact with supervisory agencies and rehabilitative programs, over an extended period of time.

Part 3: The ‘Specialty Sentencing Court” as a Problem-Solving System

The idea that sentencing courts ought to be special and distinct entities is not a new one. There are and have been many urban jurisdictions that deal with sentencing and/or probation violations with full time specialty courts. As with the early drug courts of the 1980s, the purpose of special sentencing/probation courts is often to streamline the process and move the offender through as quickly as possible. Concern for how the offender can be best prepared for a return to community with appropriate supervision and/or treatment was and is often overlooked (“Reentry Drug Courts”, National Drug Court Institute Monograph Series, No. 3, “Reentry Drug Courts”, JTauber, circa 1999).

Existing sentencing or probation courts should have the responsibility to do more. Like other problem-solving court systems, Sentencing and/or Probation Courts need to create a bond between offender and the court, that among other things, reminds both of their obligations, one to the other. Special Sentencing Court Systems need to deliver evidence-based sentencing practices, processes too complex and demanding for even the most dedicated individual judge. ( “Arming the Courts with Research: Ten Evidence Based Sentencing Initiatives to Control Crime and Reduce Costs”, a PEW monograph, Judge Roger Warren, ret.)

The best Problem-Solving Sentencing Courts will supervise through separate tracks, as do most problem-solving courts in large urban jurisdictions. The Drug, Mental Health, and DUI Courts, though often presided over by the same judge, separate out the offender by the nature of the problem that the offender faces. Though the offender may have more than one serious issue, different problems call for different resources, information, staffing and treatment.

The Veterans Court provides a particularly good model for the Sentencing judge. The Veterans Court is able to deal with the “Whole Person”. An individual is directed to the Veterans Court because he or she is faced with a criminal case, not because they have a particular issue or problem. The Veteran’s Court is prepared to deal with any and all issues facing the Veteran. To that extent, the Veteran’s court is a particularly good model for a “sentencing court”. The Veterans court mets out appropriate responses, as a sentencing courts should, dealing with many different issues, and providing the appropriate supervision and services as required.

Judge-Driven Sentencing Systems: Part 4

Sometimes it’s important to restate the obvious. The courts are the traditional place for sentencing and monitoring the supervision of offenders under their jurisdiction. Judges have husbanded those powers like no others. It’s therefore somewhat disquieting to find some states turning sentencing jurisdiction over to other agencies of government, even ones that are considered partners within the criminal justice system.

Nearly twenty years ago, when “Drug Courts: A Judicial Manual”, was published (JTauber, California Center for Judicial Education and Research,1994), it was noted that future drug courts (and ostensibly other courts modeled after drug courts) would need to create fully integrated systems centered on the court, to create the next generation of effective drug courts.

But even in a system built on collaboration and partnership, it was noted that “The courts stand in a unique position among service agencies; they are at the fulcrum, where agencies meet. Participating agencies are used to working closely with or under the supervision of the courts” (p.29).

Two decades later, whether applied to drug abuse or recidivism, those words hold true. Drug Courts and other special courts have proven the efficacy of judge-driven problem-solving courts. Handing over sentencing and/or monitoring of community supervision to probation or parole, custody or community-based agencies, isn’t smart or efficient, or cost-effective. Special Sentencing Courts need to work closely with their criminal justice and community partners, but also need to remain the focus of that circle of intervenors, retaining final control over the sentencing and supervision of the felon.

Court Monitoring of Sentence Tracks: Part 5

Courts can deal effectively with all their sentenced felons, by developing comprehensive “evidence-based sentencing systems” (see Arming the Courts with Research: , Roger Warren, Pew, 2009). Traditionally, we classify, categorize, and sort felons into appropriate groupings at every step of sentencing process. The Sheriff decides an inmate’s housing category. The probation departments recommends whether a probationer should be intensively monitored or placed in a banked case load. The court determines whether a felon is to be placed on probation or sent to prison.( Development and Implementation of Drug Court Systems, JTauber, NDCI,1999)

Today’s problem-solving courts have led the way in in the use of assessments (and other evidence based sentencing practices) to improve our sorting or categorizing and thereby our sentencing outcomes. The court and its systemic partners determine if an offender needs special rehabilitation, treatment, or education as part of the sentencing process. So a DUI offender with a third offense might require a residential alcohol treatment program, the domestic violence offender, an extensive series of violence reduction classes, and the drug offender, completion of an appropriate drug treatment program. In each instance, the court will continue to monitor the offenders at progress report hearings until the relevant conditions of probation are completed.

To optimize the effectiveness of a sentencing court’s monitoring of all felony sentences (see:Systemic Approaches to Sentencing: Part 3), we now use a more comprehensive process, a validated risk/needs assessment, to sort the offenders into appropriate tracks. A felon is determined to be a low, medium, or high risk offender. Depending on that determination, an individual is placed in different probation, treatment or rehabilitation tracks, with the court actively monitoring those tracks on a regular schedule over the term of probation (and in some cases parole). In effect, a “special sentencing team”, led by the sentencing judge, follows all offenders placed in sentencing tracks, as they move seamlessly through sentencing and custody (where ordered) and into the probation process.

It should be remembered, that though all felons are categorized and placed in tracks, that very process is intended to increase the court’s effectiveness, by limiting the court’s contact with the low risk/low needs offenders. If the sentencing court is to effectively deal with all felons, it will need to distinguish between those who require the court’s attention and those that are best left alone. Substantial savings in time, staffing, and resources lie in the court’s effective and appropriate tracking of sentenced offenders.

The Components of the Sentencing Track: Part 6

Diagram 1 represents two separate segments. The first ( “Plea” arrow to “Custody” arrow) focuses on the need to categorize, sentence, and track offenders, with a minimum of staff and resources. Tracks are essential to the system as the court will sentence and monitor offenders with very different risks and needs. A sentencing team with a different skill set is required to deal with low risk/diversion participants than with high risk/violent offenders (as a different team skill set would be required for Drug as opposed to Domestic Violence Court).

We know from the scientific literature (“Understanding the Risk Principle”), that mixing low and high risk offenders is counter-productive at best. That same dynamic works in the court room. Where possible, it’s best to keep participants with different risk levels apart. It’s also more cost-effective. Why have full staff at every session when you can substantially reduce the number of staff by sorting offenders by risk and need. When you create a participant track with few housing, job, or family issues, experienced staff in those areas can best use their time elsewhere. The savings would be substantial if case managers are designated to be in court once a week for a single track, rather than required to attend daily sessions. The corollary to that proposition is that it may be more economical to work with offenders from different sentencing categories (probationer, parolee, divertee, etc.) where the more important and relevant issue is there problem issues and reasons to recidivate, and/or criminogenic needs.

The second part of the diagram (from “Front End Jurisdiction” to Front End Reentry Court”) focuses on the potential for an “Early Intervention”. We focus on the front end because almost all states give their courts a window to recall the felon from prison within a relatively short time period (typically 4 to 12 months). Where courts are willing to use their statutory authority, serious and/or high risk offenders can complete a rehabilitation program over a short jail or prison term and avoid a long prison sentence. The opposite is true for felons sentenced to long prison terms (or even medium terms of 1 to 3 years). In most states, there is relatively little opportunity for a court to exercise authority over the “Back End”, as the felon, typically returns to the community under state supervision (see: Front Loaded Court Based interventions).

Decision Making in a Sentencing System: Part 7

The diagram a the beginning of this article, represents the first half of a sentencing system envisioned, allowing us to take a closer look at decision making in an evidence based sentencing system (Systemic Approaches to Sentencing: Part 6):

Offender Tracks are normally the province of Probation or other supervisory agencies. When used at all, they reflect internal decisions in determining the level of supervision and treatment appropriate for a probationer. With validated Risk/Needs Assessments available, the final decision as to court related tracks ought to be left to the court, based upon the recommendations of the full sentencing team. Court tracking is essential to keep offenders with similar risk and needs together, maximizing the opportunities for building positive relationships with the court and participants and limiting the negative consequences of mixing offenders with different risk levels. The court will need to schedule tracks when required staffing and resource personnel are present. Optimally, the only personnel present at all sessions will be the judge, clerk, and court manager.

As described in the demonstrative Diagram, the following evidence-based tracking system is offered for your consideration:

a. A risk assessment is completed even before sentencing and optimally before a plea is taken so all parties will have an understanding of the sentencing issues early on. (ideally, the level of treatment/rehabilitation or appropriate track designation should not be the subject of a plea agreement).

b. An individual may be given the opportunity to accept pre-plea Diversion (often called District Attorney’s Diversion). Once a complaint is filed, the court has substantial control over pre-plea and post-plea felony Diversion, as well as pre and post-plea Problem-Solving Courts. A Diversion or Problem Solving Court Court judge typically takes a plea, sentences the offender, monitors the offender over the course of the program (including in-custody progress), and presides over their graduation from the program.

c. The lead judge (or a designee) takes the plea in most other felony cases, reviewing the risk/needs assessment already completed, and sentences the felon either to probation or to prison (if the offense is violent or the offender a danger to the community). If the offender is appropriate for probation, the sentencing judge will decide whether the felon should be placed in a low, medium or high risk supervision track. Depending on the number of offenders and resources available, there could be sub-tracks within each risk category (when offender’s needs differ substantially in criminogenic attitudes and beliefs, gender concerns, drugs or alcohol problems, mental health issues, housing, job and/or education needs, and family/ parental issues)

1. Low risk offenders; Probation (banked file): Where the offender is neither a risk to society or has special needs, the court might see the offender once, shortly after probation placement, focusing the offender’s attention on probation compliance, and only see the felon again, if there is a substantial change of circumstances or graduation (note: Diversion contacts are often as minimal).

2. Medium risk offender, Probation (straight community corrections); Where the offender has a medium risk of re-offending and has special criminogenic needs, the felon would be placed in a track on a regular court schedule. Compliance in this track would require completion of cognitive behavioral and other rehabilitation services, with compliance resulting in substantial incentives and rewards. Compliance will allow the court to back off from contacts with probationers (unless changed circumstances or graduation)

3. High Risk offender, Probation (often a substantial jail term); Intensive supervision requirements might include attending court sessions on a weekly basis (remaining in court until all participants have been seen), a minimum of twice weekly contacts with a case manager, intensive cognitive behavioral therapy sessions, and prosocial activities for at least 40 hours per week (for at least 90 days)

On the far right is an article regarding an election between three candidates competing for Drug court judge in Fayetteville Arkansas (click on: Washington county). When I started the Oakland F.I.R.S.T Drug court in 1990 (Fast Intensive Rehabilitation, Supervision and Treatment), there was no one to compete with because no one knew what a drug court judge did. When they learned what the job entailed, few were particularly interested in being one. Today there are over 2,644 Drug Courts (and drug court judges) and an additional 1099 Problem-solving courts in the U.S.

From those numbers, it would appear that we’re on our way to a future dominated by Problem-Solving courts. While it’s true that states are building new Problem-Solving Courts, but they’re also severely limiting the number of participants. It is estimated that no more than two percent of all felony offenders who are sentenced enter into a problem-solving court.

To have a real impact on the criminal justice system, we will need to deal with all sentenced felony offenders (and perhaps some misdemeanors). Doing that will require a very different sentencing model than exists today. All convicted felons would need to go through a validated risk/needs assessment to determine their level of risk to recidivate and consequently the intensity of supervision and treatment required. Because we can predict with greater accuracy who are the high risk offenders, we can concentrate our resources on those individuals. Of course, the corollary is that the low risk offender would receive little or no supervision or treatment, as science tells us that the alternative would only increase their level of recidivism.

I am referring to an ”evidence-based sentencing system” that would engage those offenders that require it and leave alone those who do not. A very selective and cost-effective model that has been tried in a very few jurisdictions, and has the promise of revolutionizing the sentencing process. We are entering new era, ultimately far more important than the one begun 20 years ago. It will be critical to keep our eye on the goal of systemically working with all felons and not just drug-offenders. And to accept the challenges posed of providing evidence-based sentencing systems for all.

Reducing Prison terms through Front-End Sentencing: Part 8

The diagram at the beginning of this article, also represents the second half of a sentencing system envisioned, allowing us to use an evidence-based sentencing system as a means to keep serious (but non-violent) offenders from serving long prison terms (Composition of a Sentencing Track: Part 6).

As described in previous articles (see: Front-Loaded Court Based interventions), the front-end of a prison sentence provides the only substantial opportunity a court has to effect a prison term, once a felon is sentenced. Few courts use that statutory authority to return the felon from prison. When used at all, the authority is often applied in a non-systemic fashion, with individual judges operating on their own.

“Front-End Systemic Approaches” to long prison terms described here, (compare: Decision Making in a Sentencing system: Part 7) presents an opportunity to use graduated sanctions rather than immediate prison sentences for serious, but not-violent offenses. Such Front-End Systems can be structured in different ways. Some courts may include non-prison sentences (typically county jail or community corrections programs) as part of an “alternatives to prison” system.

Systemic approaches to “Front-End Alternatives to Prison”, might start with a Community Corrections level alternative sentence. With new offenses and/or serious violations of probation, they might move up to a county jail alternative, and finally to a short term prison sentence in lieu of a long term prison sentence. Depending on the seriousness of the offense, an offender might start a ”Front-End” Intervention at any of the three levels described. The flexibility inherent in a three tier front end/early intervention system is impressive, as is its ability to respond to the safety of the community and the needs of the offender:

A. Community Corrections Sentence in lieu of Prison: Less often used than other alternatives, this community based alternative to prison (typically residential treatment or correctional housing while an offender receives education, job training or employment), allows the judge to closely follow the offenders participation in a community based program, providing incentives or sanctions as appropriate. With successful program completion, the participant is returned to the community to continue supervision and rehabilitation under court authority. [Note: this alternative can be the first of two used before the offender is ordered to serve any prison sentence]

B. County Jail Alternative: This second tier “Front End Prison Alternative” can better emphasize the risk that the felon has of being sent to prison. Like the “Community Corrections Alternative, the County Jail Alternative allows close monitoring by the sentencing judge, appropriate incentives and sanctions, and a return to the community for further court supervision.

C. Front-End Prison Term: This ought to be thought of as a felon’s last opportunity to avoid a long prison term. Depending on the seriousness of the offense, some jurisdictions will start the Front-End Sentencing process with a prison term (skipping over possible Community Corrections and County Jail level interventions), hopefully reducing a long term sentence to a relatively brief 4 to 12 months in prison, and returning the felon to the community to complete the sentence under court supervision.

Evidence-Based Sentencing Systems are Cost-Effective: Part 9

The previous eight articles in this series are testimony to the potential of evidence based sentencing systems. Scientific and technological advances now make these systems cost-effective as well. The most cost intensive aspect of any evidence-based system are the court hearings for felons sentenced to local custody and/or supervision. There is a misconception, that in an evidence-based sentencing system, all felons would be seen in court on a regular basis (as most problem-solving courts tend to do). But science and technology has provided us with strategies and solutions that allow us to substantially reduce the need for additional court sessions and staff (the “Risk Principle”).

Validated risk/needs assessment tools developed over the past ten years allow us to determine a felon’s risk levels and how to best deal with the offender ( see “University of Cincinnati Study on Risk Principle”) We now know that intensive supervision for low to medium risk offender (involving multiple appearances before the court) actually increases their levels of recidivism. In some jurisdictions, that understanding may actually reduce the total number of court appearances, as only those who have been determined to need intensive supervision and court monitoring would receive it. Felons who are traditionally “banked” as low-risk probationers would almost certainly be excluded. Those offenders who are considered medium risk offenders might be seen by the court on a very limited basis (perhaps one court appearance after beginning their jail sentence, with a second at the start of active probation supervision and a third at the completion of successful probation supervision). Depending on criminal background, history of violence, extent of imprisonment and other relevant factors, high-risk felons would be placed in an appropriate supervision and court monitoring track. (see video at bottom of article, for interview with Reentry Court judge Jeff Tauber, on the intensity of supervision and rehabilitative track required by serious and/or violent high risk parole violators)

A more universal fiscal concern relates to the over-staffing of problem-solving courts. The fact that many courts have more than a dozen employees attending staff meetings and court sessions is a major financial obstacle to the expansion of evidence-based sentencing systems (and other problem solving courts as well). My experience as both a drug court and reentry court judge suggests problem-solving courts are often over-staffed ( see: A Minimalist Reentry Court for Recessionary Times).

My Drug Court staffing in 1990 (admittedly a long time ago) had two persons present, the probation officer personally responsible for offenders to be reviewed, and myself. In a more recent experience on the Bench (2010-2011) , the San Francisco Parole Reentry Court operated with a staff of five; judge, program coordinator, case manager, defense attorney, and parole officer. It should be acknowledged that every problem-solving court has its own staffing requirements, but the tools described above can also help keep court personnel to a minimum.

The development of risk/needs assessment tools allows us to better categorize probation/parole offenders, placing them in customized court tracks, limiting the court time of program specialists, to sessions where their skills are truly needed. Similarly, technology allows us to share information and communications between program personnel and staff, limiting the need for those present in court.

Finally, even problem-solving courts with significant operating cost, have shown themselves to be cost-effective (see California Study), substantially reducing custody and other criminal justice costs, and providing enormous savings to the community as a whole. This will undoubtedly be the case for evidence-based sentencing systems as well.

Dealing with the whole person in sentencing: Part 10

If you follow the comments of governors and other state policy makers these days, it appears that they have signed on to the notion that drug courts are the answer to prison overpopulation, high crime rates, and increased recidivism (and that may be the short list). In reading about their support for drug courts, I am cheered by their adoption of an important innovation that I along with others pioneered over twenty years ago. And I am disheartened by their misunderstanding of the significance and applicability of drug court.

As described by Dr. Doug Marlow, at the 18th Annual NADCP Conference in Nashville (see: NADCP argues for Evidence-based tracks), most drug offenders are not drug dependent and shouldn’t be part of an intensive drug court program. In fact, according to Dr. Marlow, 60 to 80% of drug offenders do not need a drug court’s intensive treatment. The majority of criminal offenders need to be treated as a whole person (not just a drug abusing person). As tempting as it may be to lock onto drug treatment as a silver bullet that works with all offenders, it isn’t an effective or cost- efficient tool for most criminal offenders (or even most drug offenders).

However that should not conclude our analysis. If you look at the scientific literature on evidence based sentencing practices, you’ll find that medium to high risk offenders have substantial criminogenic needs that need to be addressed, even if they’re not drug related.

“Criminogenic Needs” are functional impairments that if not treated, will increase the risk of further criminality. The top four such needs are a history of anti-social behavior, anti-social personality factors, anti-social cognitions/attitudes, and anti-social peers. Surprisingly, drug abuse is a second tier criminogenic need that only becomes a central concern if the offender is truly drug dependent or addicted., Otherwise, substance abuse treatment ranks behind such second tier criminogenic needs such as family and/or marital stressors, employment and/or education deficiencies, and lack of pro-social leisure activities.

In practical terms, it appears that we over-treat drug abuse and pay too little attention to cognitive behavioral needs and rehabilitative therapies that have proven success in dealing with them. In essence what Dr. Marlowe and his scientific brethren have been telling us is Drug Court is not the answer to most offenders’ crimonogenic needs (although the better drug courts do not neglect them).

Certainly drug courts can be modified (as Dr. Marlow suggests) to deal with the majority of criminal offenders, whose drug usage is not a primary criminogenic need. But it should be clear to all, that doing so may negatively impact drug courts and appropriate participants As the old saw goes, if you just treat a criminal offender’s drug abuse, you might just create a healthier criminal. Better to deal with the whole person, in an evidence-based sentencing system, where their individual levels of risk and need are determined, and the appropriate supervision and treatment responses applied to them..

Dr. Doug Marlowe, NADCP Director of Science and Law is a clinical psychologist and attorney, widely acknowledged, as the foremost authority on the science behind Drug Courts and evidence-based Drug Court systems. At the NADCP conference in Nashville, he spoke at a number of workshops, attended by hundreds of attendees and moderated a plenary panel session whose participants were a who’s who of the drug court and drug treatment field (“Reconstruction After the War on Drugs”). His two part Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheets, Targeting the Right Participants for Adult Drug Courts and Alternative Tracks in Adult Drug Courts: Matching Your Program to the Needs of your Clients, were the only documents included along with the conference agenda, provided to nearly 4500 attendees.

In his presentations and two part Fact Sheets he laid out a clear message for the drug court and the criminal justice field in general. Drug Courts are not for everyone. Only those individuals who are drug dependent ought to be placed in a drug court. According to Dr. Marlowe, sixty to eighty percent of drug offenders in the criminal justice system, are drug abusers, not drug dependent, and don’t belong in a drug court.

In Fact Sheet II, Alternative Tracks in Adult Drug Courts: Matching Your Program to the Needs of your Clients, Dr. Marlowe further explains that developing alternative tracks in drug courts for non high-risk offenders probably make good sense. “In some communities the drug court may be the most effective, or perhaps only, program serving as an alternative to incarceration”. He concludes, “If a drug court has such compelling reasons to serve low-risk or low-need individuals, it should consider making substantive modifications to its program to accommodate the characteristics of its participants”. The document then describes “a conceptual framework and evidence-based practice recommendations for designing alternative tracks within a drug court to serve different types of adult participants”. All of this information should be of great interest, not only to the drug court practitioner, but to those interested in evidence-based sentencing systems, that provides appropriate tracks for different offender populations. In fact, both documents ought to be closely read for their import to sentencing in general.

Evidence Based Sentencing as a Hybrid System: Part 11

Evidence-Based Sentencing Systems have been described in this series as problem-solving structures. More accurately they are hybrid courts that share the characteristics of traditional sentencing courts as well as rehabilitative problem solving courts. While they emphasize the need for collaboration, they often start off in a traditional adversarial proceeding. This is particularly true when individuals are convicted of serious or violent offenders.

In those cases, the court correctly views their primary responsibility as protector of the victim and community. Evidence-Based Sentencing Systems, as well as more traditional sentencing courts, incapacitate the violent and/or serious felon so they cannot continue their criminal activity, sentence to deter others from committing similar acts, and provide retribution against the offender who has done serious harm to the victim and community. Prison is a probability and even a necessity for many of these serious and violent offenders.

Evidence-Based Sentencing Courts move into problem-solving mode as the felon prepares to reenter the community. In Evidence-Based Sentencing Courts, judges and their teams develop effective structures that apply to all offenders sentenced in their jurisdiction (not just the non-violent). In fact, the structure inherent in an evidence-based sentencing team is designed to hold the offender, as well as collaborating agencies and community programs accountable for their effectiveness or lack of same. At the time Drug Court and Problem-Solving Courts were first being developed, it was noted that, “In a “structurally accountable system”, participating agencies share program responsibilities and are accountable to each other for program effectiveness, with each participant directly linked to, dependent on, and responsible to the others (J Tauber, California Center For Judicial Education and Research Journal, Drug Courts: a Judicial Manual, Summer 1994).

In other words, If evidence-based sentencing practices are employed, coordination among relevant agencies and community organizations remains essential. Sentencing tracks are required to more effectively sentence and monitor offenders with very different risks and needs. While the sentences may be very different, the same level of coordination and collaboration is required when sentencing, monitoring, and rehabilitating the serious and/or violent offenders, as it is for the non-violent offender.

Back to the Future: Evidence Based Sentencing Systems

The 12 part series on Evidence Based Sentencing Systems (see: Evidence Based Sentencing Systems) concludes as it began, with an admonition to recognize that technology and science have changed the nature of the sentencing process, What is needed is a more comprehensive and systemic approach that recognizes the advances made in sentencing, from risk/needs assessments and cognitive behavioral therapies, to the development of hybrid sentencing sysems that employ traditional as well as problem-solving practices.

We need to look beyond conventional responses to criminal behavior, acknowledging that our over-reliance on imprisonment has been a tragic mistake. The science and research advances of the past ten years should inform the sentencing decisions we make. But we should also look back into history. The prison system in this country is little more than 200 years old. Up until that time, custody as a response to criminal behavior was largely unknown and community control exerted extraordinary influence over the individual. We need to reestablish the primacy of the community through our sentencing and rehabilitation models, in essence going “Back to the Future” (The Drug Court judicial Bench Book, Chapter 1, Drug Courts: Back to the Future; J Tauber, NDCI, 2011)

We are confronted with new evidence-based sentencing practices that demand a fresh look at a very old paradigm. We need to acknowledge the central idea of evidence-based sentencing, that sentencing demands a systemic team based approach, and ultimately more effort and time than a single judge can provide. Problem-solving courts provide the structure for a hybrid system, where team based sentencing systems are capable of providing continuing sentencing processes, probation and court tracks, risk/needs information, and rehabilitative capabilities that protect the community, yet address for the offenders criminogenic needs.

We will be challenged in ways that we never expected. Our concepts regarding the treatment of non drug using offenders, drug abusers versus drug dependent offenders, low risk offenders versus low to medium risk offenders, all demand that we rethink basic sentencing and rehabilitative concepts. For those willing to open their eyes, Evidence Based Sentencing Practices can open the door to better and more cost effective sentencing.