Part 1: Evidence-Based Sentencing Practices

Last week I wrote an article suggesting the need for “Systemic Approaches to Sentencing” . On re-reading, I felt that the topic needed a more comprehensive explanation. So this is the first of a series of articles dealing with the need for systemic approaches to felony sentencing. In 2009, the PEW Center for the States published an excellent treatment on Evidence Based Sentencing Practices (EBP), authored by Judge Roger Warren (ret.), President Emeritus of the National Center for State courts,“Arming the Courts with Research: Ten Evidence Based Sentencing Initiatives to Control Crime and Reduce Costs” (click on the figure on the left for copy of article).

Last week I wrote an article suggesting the need for “Systemic Approaches to Sentencing” . On re-reading, I felt that the topic needed a more comprehensive explanation. So this is the first of a series of articles dealing with the need for systemic approaches to felony sentencing. In 2009, the PEW Center for the States published an excellent treatment on Evidence Based Sentencing Practices (EBP), authored by Judge Roger Warren (ret.), President Emeritus of the National Center for State courts,“Arming the Courts with Research: Ten Evidence Based Sentencing Initiatives to Control Crime and Reduce Costs” (click on the figure on the left for copy of article).

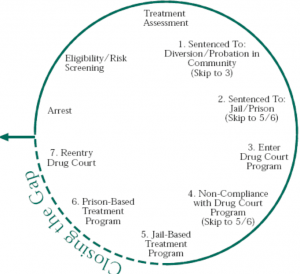

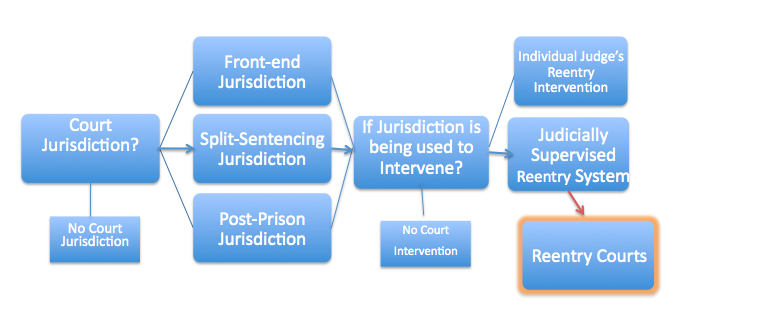

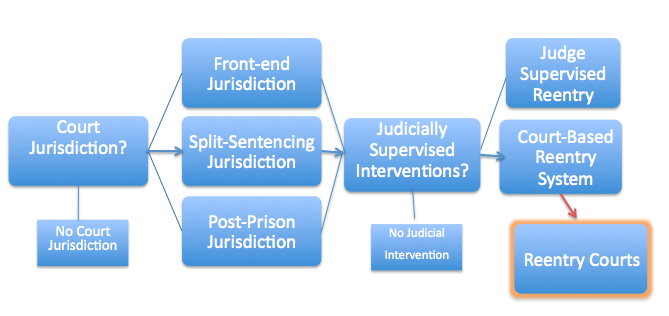

To summarize, nearly all sentencing courts are in essence, reentry courts (or court based reentry systems), and ought to be structured to facilitate the ultimate return of the offender to the community as a non-recidivist, productive citizen.

According to the PEW Monograph, every sentencing ought to take into account the most recent research, described as Evidence Based Practices (EBP). Those sentencing principles, (as described by the PEW Monograph) state that (1) Reduced Recidivism should be an immediate goal of sentencing, (2) Recidivism Reduction Options be available to the Court, (3) Sentencing be based on Risk/Needs Assessments, (4) Community Corrections be Evidence Based, (5) Services and Sanctions be integrated, (6) the Court be aware of Available Sentencing Options, (7) Court Officers be trained in EBP, (8) Court responses to probation violations be immediate, certain, consistent and fair, (9) Court hearings be used to provide incentives to motivate Offender Behavior Change, and (10) the Court Promote Collaboration among Criminal Justice Agencies.

Clearly, individual judges and courts will have have difficulty implementing many of the proposed initiatives. Only a systemic problem-solving approach is likely to successfully implement “Evidence Based Sentencing Practices”. (PEW declares as much on page two of the monograph; “the failure of mainstream sentencing policies….. has motivated many state judges, prosecutors, and corrections officials to establish specialized ‘problem-solving’ courts over the past 20 years to reduce recidivism”). Expecting individual judges to independently develop the resources, skills, and competencies to become proficient in Evidence Based Sentencing Practices is unrealistic.

That does not mean that every court needs to have the same level of resources, staffing or sentencing options. The question for most jurisdictions is what level of Evidence Based Sentencing Practices can they incorporate into their court, and that is appropriate for their community. A judge in a rural jurisdiction will have vastly different sentencing needs than a city with dozens of judges. And a low risk offender will have a very different relationship with the court than a high risk offender or an offender with a violent history.