July 25, 2014

My interest in crime and punishment began early in my career. After graduating from Boston University Law School in 1971, I spent 16 months traveling around the world, visiting over 40 nations. My travels weren’t focused on criminal justice issues, but I found myself drawn to how different cultures dealt with social deviation. In 1988, before taking the bench as a judge, I spent four months in the South Pacific; this time visiting courtrooms, judges, jails and prisons, focusing on how Polynesian and Maori cultures dealt with criminal conduct.

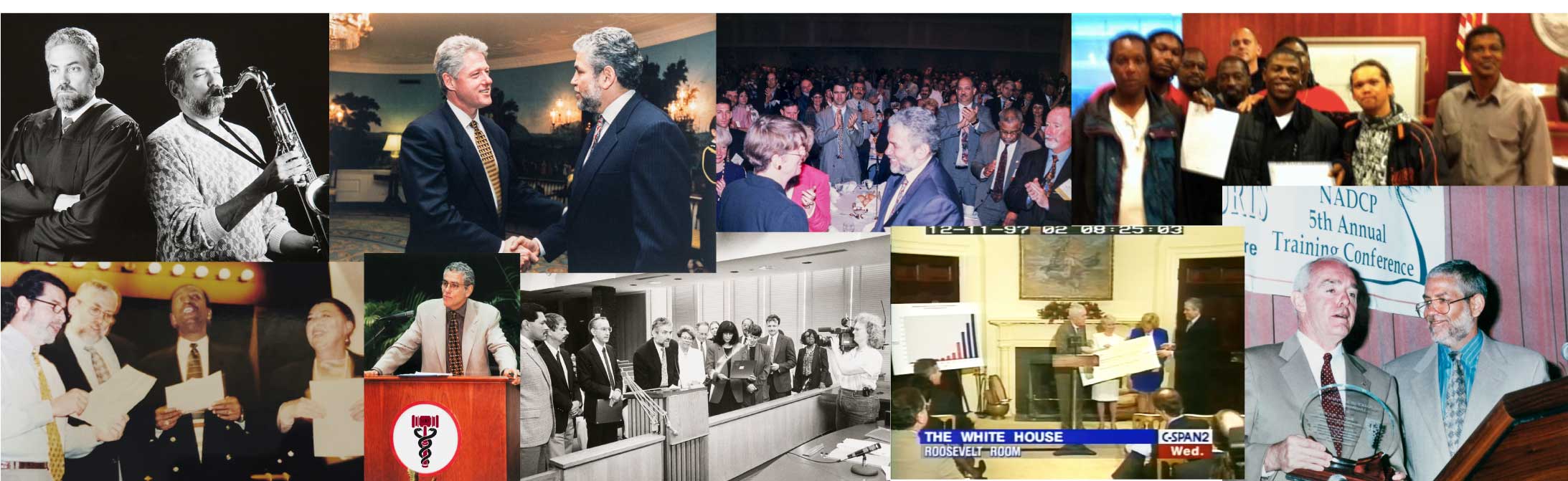

In the 1990’s, one of my priorities as NADCP’s founding President, was to see that the nascent drug court field did not collapse into a more punitive and destructive system than that which had existed before. At the time I was painfully aware of the shortcoming of some of our drug courts. Jurisdictions created drug courts for small numbers of offenders, with minimal or nonexistent drug dependence, and an over-reliance on non-therapeutic custodial sanctions. It was a direction that I strongly opposed and NADCP made a major effort to counter (and did so successfully in 1997 with the publication of “Defining Drug Courts: Key Components”)

These issues were unfortunately magnified at the international level. While the drug court model was adopted successfully in westernized nations based on the english legal system (specifically Canada and Australia), the idea that they could be easily adopted in traditional, third world countries was a somewhat fanciful notion. International Drug Courts provided a level of prestige for the U.S. model (especially before the Congress and state legislatures), but didn’t catch on in a significant way in non-westernized nations. Societies that didn’t have treatment programs, trained clinicians, drug-testing, or probation systems, let alone decent housing or clean water, would have a hard time replicating an American drug court model.

Though I traveled widely in the 1990’s on behalf of NADCP and Drug Courts across the globe, it was with some skepticism about expanding drug courts internationally and an emphasis on what other cultures could devise that would accomplish the goals of drug courts, without actually adopting the model itself.

…………………………………………………………………