THE BEST OF: First published in February of 2012, John Tunheim, the Thurston County District Attorney described the “Drug Court Model” as one of the “one of the most remarkable innovations in criminal jurisprudence since trial by jury [emphasis addded].

The article, “Drug Court turned justice system on its head – and it worked”, published in the Olympian on Feb. 29, 2012, by Chief Proscuting Attorney Jon Tunheim for Thurston County Washington, came across my desk some months ago. I was stunned by the force and conviction of the writer, And while plaudits for Drug Court and its progeny, collaborative courts, are not unique, the clarity of his vison and the historic nature of the statement make it very special. I commend this article to you and encorage you to make copies and share it with friends and colleagues. It is a reaffirmation of the historical importance of the probelm-solving court, as we look to expanding it into the realm of sentencing systems:

Drug Court turned justice system on its head – and it worked

Jon Tunheim, Prosecuting Attorney, Thurston county, Washington; 2/29/12

Sometimes, I wonder how the idea for a drug court originated. I wonder about this because the creation of drug courts in the United States is, in my opinion, one of the most remarkable innovations in criminal jurisprudence since trial by jury[emphasis addded].

Why was this idea so revolutionary? One of the cornerstones of our justice system is that it is adversarial. In other words, it resolves disputes by allowing parties to present evidence and argue their case in an adversarial setting. In the end, legally speaking, someone “wins” and someone “loses.” The adversarial system, in my view, continues to be the best way to resolve legal conflicts, particularly when the conflict is about facts.

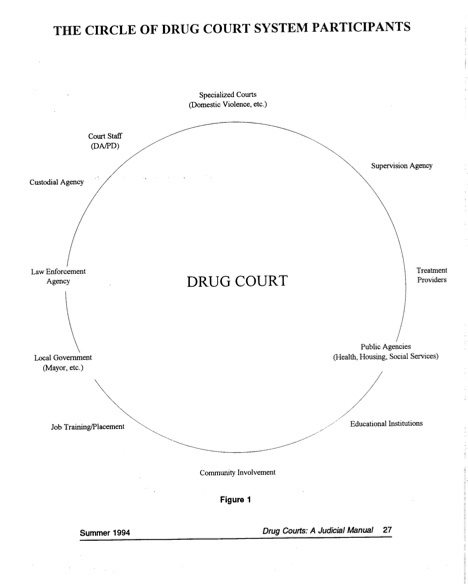

But many years ago, when Janet Reno was a district attorney in Florida, she or someone in her office suggested that perhaps we don’t need to use the adversarial system for cases where the facts aren’t really in dispute and the criminal behavior is linked to addiction. Instead of using a slow and expensive adversarial system, perhaps we create a court that is collaborative – where everyone is working together to help the person overcome their addiction and thereby prevent future criminal behavior. This idea was revolutionary because it challenged one of the fundamental principles of our justice system. I can only imagine the reaction of some lawyers to the thought of abandoning the traditional adversarial process and creating a collaborative court.

I wonder if the person who first had this idea had any notion of how successful and how important drug courts would become in the criminal justice system. The data gathered over the years is remarkable. In our own Thurston County Drug Court, only 13 percent of those who have graduated later committed another felony. In comparison, 72 percent of those who were eligible but declined to go through Drug Court went on to commit another felony. Even more surprising, those who start Drug Court but are terminated are also less likely to commit a new crime. We estimate that Drug Court has saved Thurston County taxpayers well over a million dollars of jail costs and several million dollars in societal costs for drug-free babies born to participants in the program.

Nationally, experts estimate the return on investment for an average drug court is about $2.23 for every dollar spent. Even more remarkable is the return on investment increases to as much as $3.36 for participants who are at the highest statistical risk of committing more crime. Drug courts are not just an effective way of lessening addiction-driven crime; they are also a significant long-term budget saver.

The success of drug courts over the years led us to try this collaborative model of justice for cases involving other issues that contribute to crime. Examples include mental health, veterans courts, and DUI courts to name a few. We continue to look for other new ways to use this problem-solving court model as a way to reduce recidivism.

I wonder if the person who first thought of collaborative problem-solving courts had any idea how many lives would be saved. I wonder if they considered how many people would see loved ones pull themselves out of addiction and into recovery. I wonder if they even considered how much money would be saved over the years. It truly was an idea that changed the criminal justice system forever.