Mar. 25, 2012

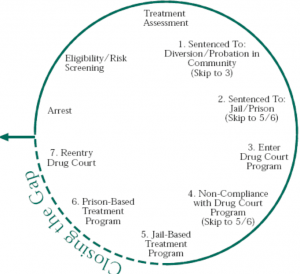

An ACLU Report (described in two articles in the Face Book Column on the far right), points to the failure of California’s Realignment Plan (under AB109), to provide incentives to counties that reduce the numbers of persons incarcerated in county jail. The report describes the state’s dismembering its Prison-Industrial Complex, while supporting the development of a Jail-Industrial Complex. It’s argues that counties that develop successful “alternatives to incarceration”, and/or send a small percentage of non-violent offenders to prison are penalized as proportionally larger funds are provided to counties that have neither adequate jail facilities or effective alternatives to custody. The counter argument is a simple admission that counties that have not used alternatives in the past and relied heavily on state prison to house less serious offenders, need immediate resources to build an infrastructure capable of working with the returning offenders, both in and out of custody (on the left; a systemic sentencing circle, JTauber, circa 1999, National Drug Court Institute Monograph Series, No. 3, “Reentry Drug Courts”)

An ACLU Report (described in two articles in the Face Book Column on the far right), points to the failure of California’s Realignment Plan (under AB109), to provide incentives to counties that reduce the numbers of persons incarcerated in county jail. The report describes the state’s dismembering its Prison-Industrial Complex, while supporting the development of a Jail-Industrial Complex. It’s argues that counties that develop successful “alternatives to incarceration”, and/or send a small percentage of non-violent offenders to prison are penalized as proportionally larger funds are provided to counties that have neither adequate jail facilities or effective alternatives to custody. The counter argument is a simple admission that counties that have not used alternatives in the past and relied heavily on state prison to house less serious offenders, need immediate resources to build an infrastructure capable of working with the returning offenders, both in and out of custody (on the left; a systemic sentencing circle, JTauber, circa 1999, National Drug Court Institute Monograph Series, No. 3, “Reentry Drug Courts”)

California needs to deal both with the lack of adequate jail resources, while creating incentives for counties to develop alternatives to incarceration. One way to accomplish that, is to develop effective risk/needs assesssment tools that can distinguish between those who are a violent and/or high-risk offenders and those who do not pose a danger to the community. Risk/Needs Assessments, once validated, provide an scientific basis for determining the risk of offenders to the community. Working with such tools, a county’s criminal justice system ought to be able to create a systemic approach to the convicted offender, that provides appropriate sentencing tracks that reflect an offender’s degree of risk as well as their criminogenic needs. In the future, counties that develop effective sentencing systems, used in the supervision and rehabilitation of felons, that reduce the jail population, ought to receive substantial financial incentives from the state ( California already has a successful state program that rewards probation departments for reductions in probationer recidivism)

We have developed evidence based practices for the sentencing of offenders (based on voluminous research), but are still reticent to apply those practices where they will do the most good, in making sentencing decisions. Rational approaches to sentencing that provide different levels of supervision, treatment, rehabilitation, and assistance for felons are attainable and in effect in some states and jurisdictions (more on that later).