May, 13, 2012

May, 13, 2012

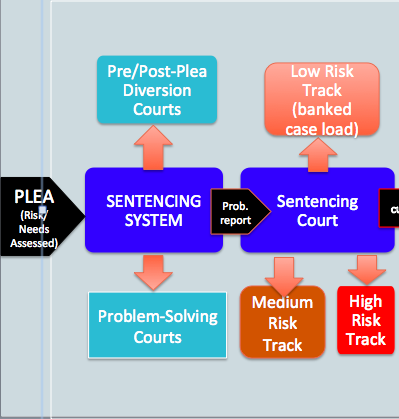

Decision Making in a Sentencing System: Part 7

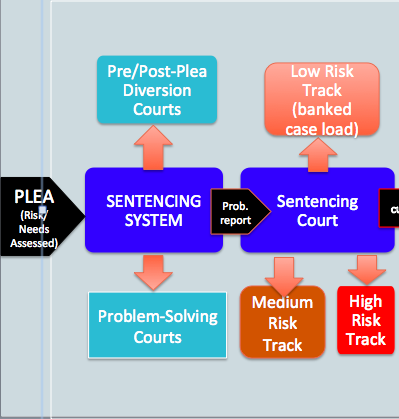

The diagram on the left represents the first half of a sentencing system envisioned, allowing us to take a closer look at decision making in an evidence based sentencing system (Systemic Approaches to Sentencing: Part 6):

Offender Tracks are normally the province of Probation or other supervisory agencies. When used at all, they reflect internal decisions in determining the level of supervision and treatment appropriate for a probationer. With validated Risk/Needs Assessments available, the final decision as to court related tracks ought to be left to the court, based upon the recommendations of the full sentencing team. Court tracking is essential to keep offenders with similar risk and needs together, maximizing the opportunities for building positive relationships with the court and participants and limiting the negative consequences of mixing offenders with different risk levels. The court will need to schedule tracks when required staffing and resource personnel are present. Optimally, the only personnel present at all sessions will be the judge, clerk, and court manager.

As described in the demonstrative Diagram, the following evidence-based tracking system is offered for your consideration:

a. A risk assessment is completed even before sentencing and optimally before a plea is taken so all parties will have an understanding of the sentencing issues early on. ( ideally, the level of treatment/rehabilitation or appropriate track designation should not be the subject of a plea agreement).

b. An individual may be given the opportunity to accept pre-plea Diversion (often called District Attorney’s Diversion). Once a complaint is filed, the court has substantial control over pre-plea and post-plea felony Diversion, as well as pre and post-plea Problem-Solving Courts. A Diversion or Problem Solving Court Court judge typically takes a plea, sentences the offender, monitors the offender over the course of the program (including in-custody progress), and presides over their graduation from the program.

c. The lead judge (or a designee) takes the plea in most other felony cases, reviewing the risk/needs assessment already completed, and sentences the felon either to probation or to prison (if the offense is violent or the offender a danger to the community). If the offender is appropriate for probation , the sentencing judge will decide whether the felon should be placed in a low, medium or high risk supervision track. Depending on the number of offenders and resources available, there could be sub-tracks within each risk category (when offender’s needs differ substantially in criminogenic attitudes and beliefs, gender concerns, drugs or alcohol problems, mental health issues, housing, job and/or education needs, and family/ parental issues)

1. Low risk offenders; Probation (banked file): Where the offender is neither a risk to society or has special needs, the court might see the offender once, shortly after probation placement, focusing the offender’s attention on probation compliance, and only see the felon again, if there is a substantial change of circumstances or graduation (note: Diversion contacts are often as minimal).

2. Medium risk offender, Probation (straight community corrections); Where the offender has a medium risk of re-offending and has special criminogenic needs, the felon would be placed in a track on a regular court schedule. Compliance in this track would require completion of cognitive behavioral and other rehabilitation services, with compliance resulting in substantial incentives and rewards. Compliance will allow the court to back off from contacts with probationers (unless changed circumstances or graduation)

3. High Risk offender, Probation (often a substantial jail term); Intensive supervision requirements might include attending court sessions on a weekly basis (remaining in court until all participants have been seen), a minimum of twice weekly contacts with a case manager, intensive cognitive behavioral therapy sessions, and prosocial activities for atleast 40 hours per week (for at least 90 days)

The next segment will look at the ability of local jurisdictions to use brief prison terms in sentencing