THE BEST OF: The following article was published on Feb. 4th, 2012. It describes the success of the San Francisco Parole Reentry Court, and opens the door to evaluations and research based on the San Francisco Model.

PDF

The San Francisco Parole Reentry Court (SFPRC) was a statutorily funded pilot project administered by both the California Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). The funding itself, some $1.5 million per county was provided by the federal government through 2009 Stimulus funding. Without going into structural detail here (to be saved for another more expansive article), I’d like to provide general information on how SFPRC was designed and implemented, as well as statistical evidence of its success.

The San Francisco Parole Reentry Court (SFPRC) was a statutorily funded pilot project administered by both the California Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). The funding itself, some $1.5 million per county was provided by the federal government through 2009 Stimulus funding. Without going into structural detail here (to be saved for another more expansive article), I’d like to provide general information on how SFPRC was designed and implemented, as well as statistical evidence of its success.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) data for the 10-month period that the San Francisco Parole Reentry Court (SFPRC) was fully operational (Dec. 2010-Sept. 2011) established that the SFPRC “return to prison” rate was 1/7th the rate of regular San Francisco parolees (a reduction of over 85% over 10 months). SF’s parolee population had 1365 “return to prison” out of its 1,686 parolees (81% of the SF parole population). The SFPRC had 8 out of 70 parolees return to prison (an 11% rate).

The most important attribute of the SFPRC were its reliance on “the court as rehabilitation community”

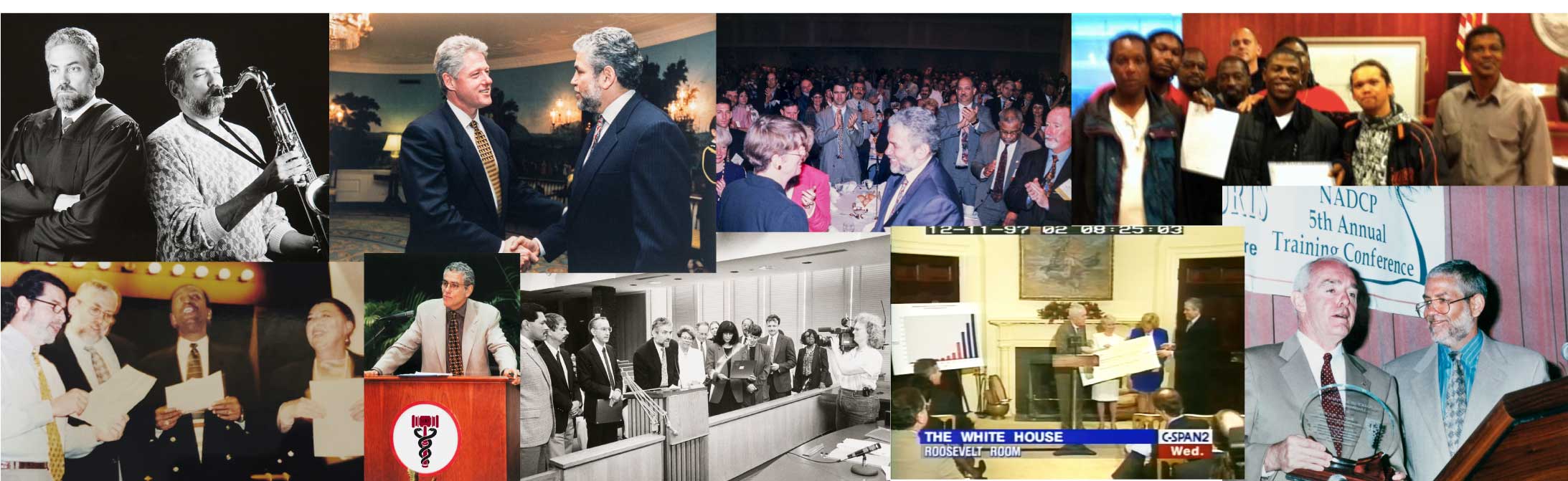

The SFPRC team and participants created a rehabilitation community that was a driving force for participant change. The court team encouraged and often joined participants in pro-social activities, treating participants as individuals worthy of respect. The court became a friendlier place; where strangers became friends and sometimes mentors, coffee and pastries were served, rehab sessions and counseling, honor roll meetings and award ceremonies, and other pro-social activities occurred. Participants were also expected to engage in the larger community via volunteerism and other activities (i.e. organizing family picnics).

The corollary principle employed was that positive reinforcement and minimal sanctions, rather than custody would be used to modify negative behavoirs”.

The SFPRC embraced a true paradigm shift, pioneering the use of positive reinforcement in reentry courts; using awards, rewards, and positive, and negative incentives to recognize accomplishments.A tangible example: The courtroom bulletin board displayed the SFPRC Newsletter, awards and certificates, letters and poetry, photos of graduation and awards ceremonies, family and friends, court picnics, and newly inducted Honor Roll members.

Minimum sanctions were used as necessary, almost to the exclusion of custody. This is especially relevant under new state law, where parole sanctions are often statutorily limited to 90 days county jail. SFPRC sanctioned 14 participants for a total of 105 days in jail over the course of the program. During that same period, SFPRC’s 70 participants achieved a 93% attendance rate, though required to attend weekly court sessions (approximately 1200 hour-long court appearances over a 10 month period).

Over it’s 15-month life ( including planning and implementation), SFPRC modeled “a minimalist reentry court for recessionary times”(see: reentrycourtsolutions.com). Though problem-solving courts” and reentry courts in particular are often accused of being wasteful, the relatively resource rich SFPRC was dealing with high-risk, serious and violent offenders, who were ultimatley far more expensive to deal with either in prison or in the community. SFPRC limited itself to a part-time judge, court coordinator, case manager, defense attorney, parole officer and clerk. It used minimal incarceration while achieving a 87% reduction in “returns to prison”. And it successfully engaged long term prisoners, recently returned to society, in rehabilitation through a court-based community.

For a one page summary of the San Francisco Parole Reentry court’s mission, design, and statistical results, see: Final 1-Year SFPRC Report Card