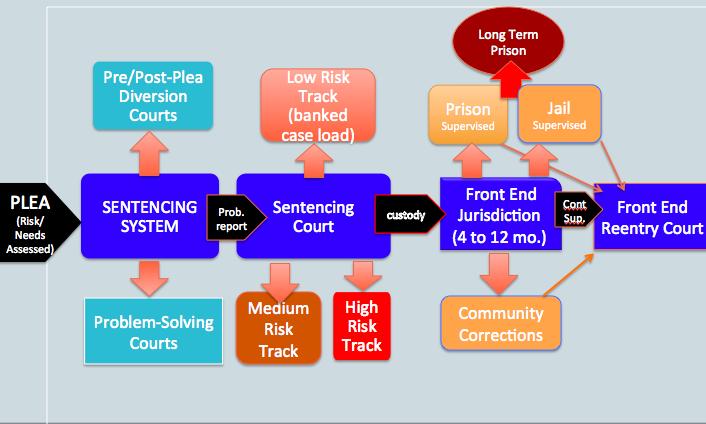

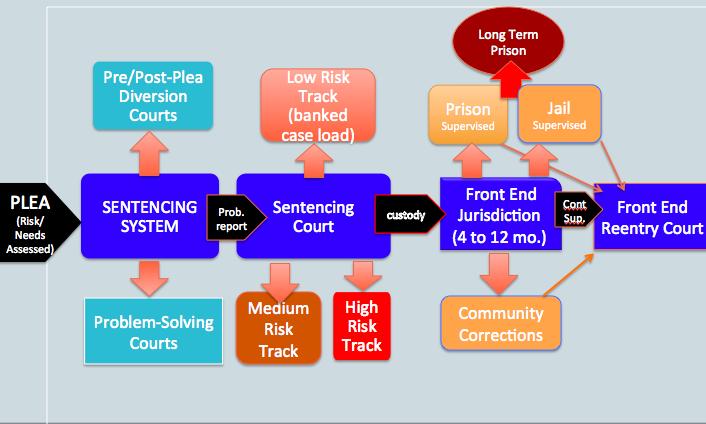

The following diagram and descriptive analysis of an Evidence-Based Sentencing System were published in September as a development tool for California Counties building realignment sentencing structures.

(A 12 Part Series on Sentencing Systems, can be found to under “SENTENCING SYTEMS” (or by clicking on the diagram below)

AN OVERVIEW OF A SYSTEMIC SENTENCING MODEL PDF

The diagram above can be thought of having two separate phases. The first (from “Plea” arrow to “Custody” arrow) focuses in on the need to effectively categorize, sentence, and track offenders, with a minimum of staff and resources. Tracks are essential to the system as the court will sentence and monitor offenders with very different risks and needs. A sentencing team with a different skill set is required to deal with low risk and diversion participants than with high risk and violent offenders (as a different team skill set would be required for Drug Court as opposed to Domestic Violence Court).

We know from the scientific literature that mixing low and high-risk offenders is counter-productive at best. That same dynamic works in the courtroom. Where possible, it’s best to keep participants with different risk levels apart. It’s also more cost-effective. Why have full staff at every session when you can substantially reduce the number of staff by sorting offenders by risk and need. When you create a participant track with few housing, job, or family issues, experienced staff in those areas can best use their time elsewhere. The savings would be substantial if case managers are designated to be in court once a week for a single track, rather than required to attend daily sessions

The second part of the diagram (from “Front End Jurisdiction” through Front End Reentry Court”) focuses on the potential for an “Early Intervention”. We focus on the front end because almost all states give their courts a window to recall the felon from prison within a relatively short time period (typically 4 to 12 months). Where courts are willing to use their statutory authority, serious and/or high-risk offenders can complete a rehabilitation program over a short jail or prison term and avoid a long prison sentence. The opposite is true for felons sentenced to long prison terms (or even medium terms of 1 to 3 years). In most states, there is relatively little opportunity for a court to exercise authority over the “Back End”, as the felon, typically returns to the community under state supervision.

Decision Making in a Sentencing System

Offender Tracks are normally the province of Probation or other supervisory agencies. When used at all, they reflect internal decisions in determining the level of supervision and treatment appropriate for a probationer. With validated Risk/Needs Assessments available, the final decision as to court related tracks ought to be left to the court, based upon the recommendations of the full sentencing team.

Court tracking is essential to keep offenders with similar risk and needs together, maximizing the opportunities for building positive relationships with the court and participants and limiting the negative consequences of mixing offenders with different risk levels. The court will need to schedule tracks when required staffing and resource personnel are present. Optimally, the only personnel present at all sessions will be the judge, clerk, and court manager. Review below the process and procedures:

a. A risk assessment is completed even before sentencing and optimally before a plea is taken so all parties will have an understanding of the sentencing issues early on. (Ideally, the level of treatment/rehabilitation or appropriate track designation should not be the subject of a plea agreement).

b. An individual may be given the opportunity to accept pre-plea Diversion (often called District Attorney’s Diversion). Once a complaint is filed, the court has substantial control over pre-plea and post-plea felony Diversion, as well as pre and post-plea Problem-Solving Courts. A Diversion or Problem Solving Court judge typically takes a plea, sentences the offender, monitors the offender over the course of the program (including in-custody progress), and presides over their graduation from the program.

c. The lead judge (or a designee) takes the plea in most other felony cases, reviewing the risk/needs assessment already completed, and sentences the felon either to probation or prison (if the offense is violent or the offender a danger to the community). If the offender is appropriate for probation , the sentencing judge will decide whether the felon should be placed in a low, medium or high risk supervision track. Depending on the number of offenders and resources available, there could be sub-tracks within each risk category (when offender’s needs differ substantially in criminogenic attitudes and beliefs, gender concerns, drugs or alcohol problems, mental health issues, housing, job and/or education needs, and family/ parental issues)

1. Low risk offenders; Probation (banked file): Where the offender is neither a risk to society or has special needs, the court might see the offender once, shortly after probation placement, focusing the offender’s attention on probation compliance, and only see the felon again, if there is a substantial change of circumstances (note: Diversion contacts are often as minimal).

2. Medium risk offender, Probation (straight community corrections); Where the offender has a medium risk of re-offending and has special criminogenic needs, the felon would be placed in a track on a regular court schedule. Compliance in this track would require completion of cognitive behavioral and other rehabilitation services, with compliance resulting in substantial incentives and rewards. Compliance will allow the court to back off from contacts with probationers (unless changed circumstances or graduation)

3. High Risk offender, Probation (often a substantial jail term); Intensive supervision requirements might include attending court sessions on a weekly basis (remaining in court until all participants have been seen), a minimum of twice weekly contacts with a case manager, intensive cognitive behavioral therapy sessions, and pro-social activities for at least 40 hours per week (for at least 90 days)

Reducing Prison terms through Front-End Sentencing

The second half of the diagram represents the use of alternatives to prison terms, allowing us to use an evidence-based sentencing system as a means to keep serious (but non-violent) offenders from serving long prison terms.

The front-end of a prison sentence provides the only substantial opportunity a court has to effect a prison term, once a felon is sentenced. Few courts use that statutory authority to return the felon from prison. When used at all, the authority is often applied in by individual judges in a non-systemic fashion.

“Front-End Systemic Approaches” to long prison terms described here present an opportunity to use graduated sanctions rather than immediate prison sentences for serious, but not-violent offenses. Such Front-End Systems can be structured in different ways. Some courts may include non-prison sentences (typically county jail or community corrections programs) as part of an “alternatives to prison” system.

Systemic approaches to “Front-End Alternatives to Prison” might start with a Community Corrections level alternative sentence. With new offenses and/or serious violations of probation, they might move up to a county jail alternative, and finally to a short-term prison sentence in lieu of a long-term prison sentence. Depending on the seriousness of the offense, an offender might start a ”Front-End” Intervention at any of the three levels.

A. Community Corrections Sentence in lieu of Prison: Less often used than other alternatives, this community based alternative to prison (typically residential treatment or correctional housing while an offender receives education, job training or employment), allows the judge to closely follow the offenders participation in a community based program, providing incentives or sanctions as appropriate. With successful program completion, the participant is returned to the community to continue supervision and rehabilitation under court authority. [Note: this alternative can be the first of two used before the offender is ordered to serve any prison sentence]

B. County Jail Alternative: This second tier “Front End Prison Alternative” can better emphasize the risk that the felon has of being sent to prison. Like the “Community Corrections Alternative, the County Jail Alternative allows close monitoring by the sentencing judge, appropriate incentives and sanctions, and a return to the community for further court supervision.

C. Front-End Prison Term: This ought to be thought of as a felon’s last opportunity to avoid a long prison term. Depending on the seriousness of the offense, some jurisdictions will start the Front-End Sentencing process with a prison term (skipping over possible Community Corrections and County Jail level interventions), hopefully reducing a long term sentence to a relatively brief 4 to 12 months in prison, and returning the felon to the community to complete the sentence under court supervision.

A team of Organization of American States (OAS) and International Association of Drug Treatment Court officials, along with national and region-wide anti-drug institutions, are hard at work, assisting in the development of drug courts in the Southern Hemisphere. Among the states that the OAS is working closely with are Barbados, Chile, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago (T&T), . Antonio Alomba leads the OAS effort to assist South American and Caribbean nations in the development of drug courts. In the training held in Trinidad, between Feb.21-23. IADTC President, Justice Kofi Barnes of the Ontario Supreme Court, led a team of drug court professionals from Canada, the United States, and the Caribbean (Jamaica specifically).

A team of Organization of American States (OAS) and International Association of Drug Treatment Court officials, along with national and region-wide anti-drug institutions, are hard at work, assisting in the development of drug courts in the Southern Hemisphere. Among the states that the OAS is working closely with are Barbados, Chile, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago (T&T), . Antonio Alomba leads the OAS effort to assist South American and Caribbean nations in the development of drug courts. In the training held in Trinidad, between Feb.21-23. IADTC President, Justice Kofi Barnes of the Ontario Supreme Court, led a team of drug court professionals from Canada, the United States, and the Caribbean (Jamaica specifically).