The Best Of: First described in April, 2013, the “ARK” project has now been confirmed to be a fully funded ONDCP sponsored initiative, hopefully providing a systemic approach to the sentencing of offenders that will be applied across the nation

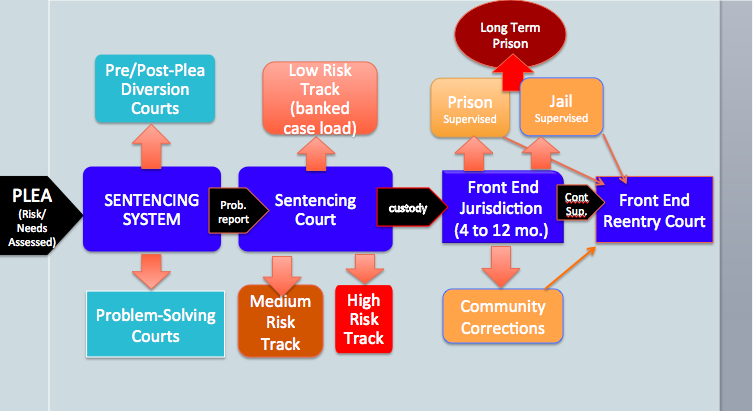

[EDITOR’S NOTE::The “ARK” program described in the press release below, is not fully defined, but seems similar to an evidence based sentencing system, described in a 12 part article, “A Model Court Based Sentencing System” published on this site last year. Specifically, its reference to “a reform framework to assess offenders and sort them into a systemic continuum of evidence-based sentencing options” would be a wonderful new initiative for drug courts and sentencing systems, in general]

The following press release is from the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP):

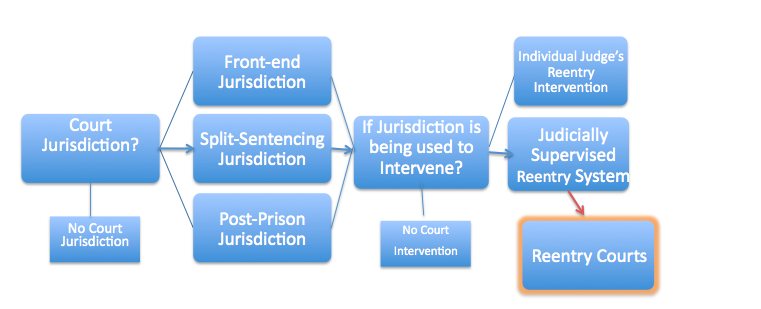

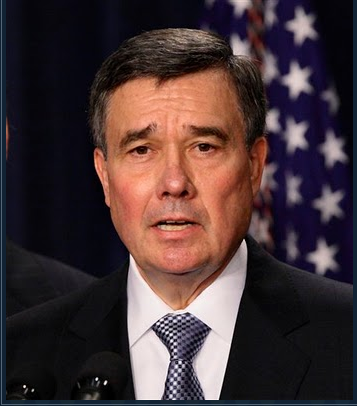

The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy Director, Gil Kerlikowske (see photo image on left of Director Kerlikowski) announced today that NADCP will receive a $1.4 million grant to expand the reach of Drug Courts and the groundbreaking justice reform model, the Annuals of Research and Knowledge on Successful Offender Management (ARK). Based on the Risk and Need Responsively theory, the ARK was designed as a reform framework to assess offenders and sort them into a systemic continuum of evidence-based sentencing options. Today’s announcement represents a groundbreaking step towards significant justice reform across all points of the adult justice system.

The National Press Club speech was attended by justice leaders and policy experts from across the criminal justice spectrum. Representing NADCP was an incredible group of treatment court pioneers covering over twenty years of alternative sentencing innovation and leadership. Joining NADCP CEO West Huddleston were Board Chair Judge Robert Rancourt, Board Member Judge Pamela Gray, and former Board Chairs Judge Lou Presenza, Judge John Schwartz, and Judge Chuck Simmons.

“Drug Court is what real drug policy reform looks like,” said ONDCP Director Gil Kerlikowske. “By giving non-violent drug offenders a chance to reclaim their lives through treatment, we can finally begin to break the cycle of drug use, crime, and incarceration in America. Every dollar we spend on supporting this type of drug policy reform pays dividends in safer and healthier communities later on.”

“Today, our vision of a solution-oriented justice system is significantly closer to becoming reality,” said NADCP CEO West Huddleston. “This funding will allow NADCP and its partners to put the ARK into practice. We remain grateful that through this funding, Congress and the Administration continues its commitment to expand the reach of Drug Courts and ensure that they remain a cornerstone of much needed criminal justice reform.”

“We look forward to taking the ARK to scale,” said NADCP Board Chair Judge Judge Robert Rancourt. “In doing so, NADCP commits to collaborating with leaders from the law enforcement, corrections, probation, prosecution, defense, substance abuse and mental health communities. Working together, we will build a comprehensive system that will forever change the delivery of effective justice in this country.”

To learn more about the ARK, watch NADCP Chief of Science, Law and Policy and ARK co-creator Dr. Doug Marlowe present during the NADCP 18th Annual Training Conference.

Professor Hale’s analysis describes NADCP as the “Champion” Non-Profit Organization in its field. What does it have to do with reentry courts and court-based reentry systems. The answer is that it does and it doesn’t.

Professor Hale’s analysis describes NADCP as the “Champion” Non-Profit Organization in its field. What does it have to do with reentry courts and court-based reentry systems. The answer is that it does and it doesn’t.