April 29, 2013

In the title of this blog and its substance, I am extrapolating on issues presented in an excellent article, “How to Make Drug Courts Work”, authored by Harold Pollack, Eric Sevigny and Peter Reuter, published in the Washington Post (April 26,2013). The issues explored relating to drug courts are almost identical to those facing other problem-solving courts or specialty courts, including reentry courts.

In the Post article, its authors lament that drug courts and other specialty courts are slated to receive $80 million with possibly little to show for it. They point out that although numerous (half of all counties claim to have a drug court), they average only 50 participants. More significantly, too many courts stick to a limited, and political cautious approach to their specialty courts. By that i mean they screen out the serious or violent offender, and work with those who need the intensive specialty court services the least. As Professor Ed Latessa has highlighted in his research at the University of Cincinati; spending money, resources and energy on low to medium risk offenders, whose offenses are non-serious and non-violent is a poor use of limited resources (see in this website: “High Risk Offenders do Better in Half-Way Houses”). As the article’s authors succinctly put it,”Drug courts could be more helpful in reducing crime and incarceration, but only if they become more ambitious and less risk-averse by taking in populations likely to serve real time”.

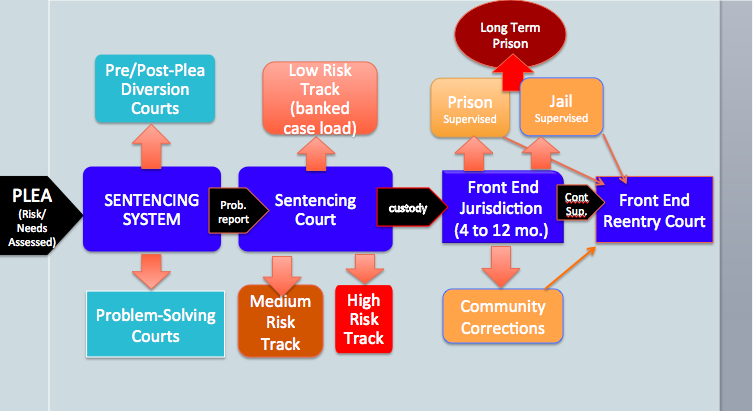

And here is where Reentry Courts come in. Reentry Courts don’t focus on drug abusers unless they have a serious drug dependency. They do focus on offenders coming out of custody who have served “real time” for serious and/or violent offenses. That is their purpose, whether there is a drug dependency or not. Keep in mind that these offenders will overwhelmingly be released with or without the serious supervision and rehabilitation services of a Reentry Court. What possible sense does it make, to work with those who pose the least risk to society and benefit the least from an intensive intervention like Drug or Reentry Court.

The authors argue that drug courts [and reentry courts by extension] widen the net of formal social control. That “Even if these drug court participants had been incarcerated, many would likely have received short terms, often in county jails, for less than a year”. It is as if fishermen were to pull in their nets and throw the big fish back and harvest the small fish. It is not logical, does not make our communities safer or serve them well. But we continue to keep the small fry, and let the big fish return to the wild.